Cheviots

Can

Take it!

By the Editorial Staff of THE SHEPHERD, January 1958.

For a real understanding of the Cheviot, we should journey in our imagination to the land of its origin – to that inhospitable strip of border country between England and Scotland called the Cheviot Hills.

Here harshness of climate and severity of terrain left an indelible mark on this breed in formative stages. There are probably few cases where a breed has been more surely and permanently “typed” by a single environment.

What was it like to be a sheep in the Cheviot Hills in those early days? Let us turn the pages of history to find out.

According to The American Shepherd (1857), “The Cheviot Hills are part of that extensive and elevated rang which extends from Galloway through Northumberland into Cumberland and Westmoreland, occupying a space from 150-200 square miles. The majority of them are pointed like cones; their sides are smooth and steep, and their bases are nearly in contact with each other… “On the upper part of that hill in Northumberland, which is properly termed the Cheviot, a peculiar and most valuable breed of sheep is found. They have been there almost from time immemorial..”

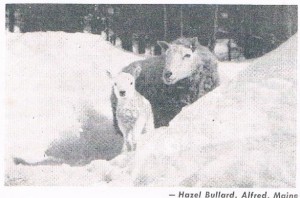

Describing the original Cheviot in 1792, Sir John Sinclair wrote: “Perhaps there is no part of the whole island where, at first sight, a fine-wooled breed of sheep is less to be expected than among the Cheviot Hills. Many parts of the sheep-walks consist of nothing but peat bogs and deep morasses. During winter the hills are covered with snow for two, three, and sometimes four months, and they have an ample proportion of bad weather during the other seasons of the year, yet a sheep is to be found that will thrive even in the wildest part of it … They have a closer fleece … which keeps them warmer in the cold weather, and prevents either snow or rain from incommoding them. They have never any other food, except when they are fattened, than the grass and natural hay produced on their own hills.”

Under these austere conditions, one would expect that the early mountains shepherds would have given their flocks every protection from the elements, yet we are told that this was not the case. In spite of the terrific storms which beset the Scottish Highlands, these flocks were expected to “root, hog, or die”, with virtually nothing in the way of shelter or winter feeding, except what they could dig up for themselves from under the snow. There where losses, of course. One sad story was reported in the Shepherd’s Calendar of that day about a storm lasting 13 days and nights with such intense cold and icy snow that 20,000 sheep in that area were reduced to a pitiful remnant of 40 wethers on one farm and 5 old ewes on another. Other stories from this period tell of the “almost incredible tenacity of life” when many sheep survived the most wicked storms, even though buried in snowdrifts so that they had to be dug out. There are reports of two sheep which lived in spite of having been buried in snowdrifts for over 30 days, during the winter of 1800.

Sixth Sense

Other shepherds wrote that the Cheviot Hills sheep seemed to sense an approaching storm and would seek what shelter they could find on the leeward side of the hills at a time “when the shepherd sees not a cloud and dreams of a wind.”

So today we find the Cheviot alert, wary, and resourceful. Its grazing pattern is unlike that of other sheep. Instead of grouping together in a frontal assault on a single area, they tend to spread out, often wandering off by themselves, singly or in small groups, not to return to the common fold until nightfall. As rustlers they have few equals. If there is vegetation to be found – above or beneath the snow – browse, grass, heather, or weed – they will find it.

What witches’ brew went into the genetic make-up of this enterprising breed is not pin-pointed for us with any degree of certainty. From the few brief accounts handed down to us through the years, we may assume that minor infusions of blood of other breeds took place from time to time, but that the whole the breed preserved a surprisingly high degree of genetic purity as a result of inbreeding.

Merinos, Lincolns, Leicesters, Southdowns, even a local breed of goat, are said to have played a part in the development of the breed – to say nothing of the native stock present in the hill country from the time Caesar’s legions brought to Britain the cultural and sheep husbandry of Rome.

Certainly, the basic beginnings of a distinctive Cheviot breed existed in the Cheviot Hills of Northern England as far back as the Battle of Bannockburn – a race of sheep described as small hardy animals with a “long white face” and other physical attributes of the present Cheviot. About 1370 considerable numbers of these “longfaces”, as they were called, found their way north from the English hills into the border country in the south of Scotland. There they mingled with and gradually displaced the primitive tan-faced sheep hat had been reared mainly for their hardiness and mutton qualities without much regard for wool. (Surviving traces of tan color in the Cheviot today are looked upon with considerable disfavor. Their origin would seem obvious.)

Monks Looked to Wool

During the four centuries that followed, much of the effort toward improvement of the breed was directed toward developing its interesting wool potential. This was the period when cattle and sheep were the chief plunder of roving bands of border thieves. But the Church owned large tracts of land in the hill country, and here large numbers of the beast sheep must have found “privileged sanctuary”. It was a scoundrel indeed who would think of profaning the land and properties of the monastery.

To the monks, weaving woolen fabrics was an engrossing occupation. What they probably saw in the Cheviot was an unusual quality of wool that would lend itself to the making of distinctive, durable fabrics.

Various explanations have been offered for the fineness of the Cheviot wool during this period. It is known that 3,000 of the famed Spanish Merinos were imported into British Isles in 1480. A like number were brought in during the time of Mary, Queen of Scots, whose Spanish husband played a significant role in the undertaking (1560). The nearby port of Berwick was a seaport of some prominence, and transporting Merinos would have been a simple matter.

However the Merino was introduced, it was soon found that it weakened the constitution of the animal, and the practice was soon stopped.

Far more dramatic is the suggestion that the peculiar quality of the Cheviot wool derives in part from a goat. Says Leggett (1947) “At time there was a variety of sheep in the highlands of Scotland that had wool of a peculiar quality, which has been traced to cross-breeding with local type of goat… Although Scottish sheep breeders apparently made little attempt to improve the quality of the local wool, yet by 1688 the woolen cloth industry of that country appears to have become really important raising the apprehension of English cloth weavers.”

The wool of the Cheviot sheep enabled the Scottish crofters to make a special type of cloth appropriately called “Cheviot”. From the breed’s early origin in the Cheviot Hills and along the River Tweed, the name “twill” or more properly “tweel” accidently became corrupted to “tweed.” Under that name, Cheviot tweed went on to earn world renown. It is considered the longest lasting of all makes of cloth.

Robson Steps In

James Robson of Belford is credited with being the pioneer improver of the mutton quality of the Cheviot sheep. His goal was a larger sheep, of earlier maturity, and better meat conformation. At his farm he undertook extensive breeding experiments. Like Bakewell, Robson toured the British countryside for individuals best suited to his program. Some of these he found in Lincolnshire where he purchased three rams from Mr. Mumby of Bartonupon-Humber. He described these as “big, close-coated sheep.” Mated to the narrow-shouldered, short -wooled ewes of the hill country, Robson brought about a vast improvement in the conformation of the animal, especially in the forequarters. Wool clip increased 20%. Rams of his Belford cross soon became very popular and were used widely all over and beyond the Cheviot Hills to improve the native Cheviot flock.

Not all efforts to improve the breed with Lincoln and Leicester blood where as successful as Robson’s. Some like the Merino infusions, tended to lower the vitality and constitutional vigor of the breed, and these attempts, too, were dropped. Ultimately, it came about that there were two breeds: the Southern Cheviot, and the North Country Cheviot, the latter a large sheep with silkier fleece; the former was a smaller, typier animal resulting from selective inbreeding and designed to retain the original qualities for which the breed was rapidly becoming famous. By 1830 this type of Cheviot had become the dominant breed in the South of Scotland, to a large extent displacing the Black-faced Highland from all but the loftiest elevations in the hills.

The earliest American importations of Cheviot sheep came to Canada in 1825. The history of the breed in the U.S. dates from an importation in 1838 by Scotch immigrants who settled in Otsego County, New York. The latter importation and the few that followed furnished the seed stock for virtually all the Cheviot flocks in this country. From all accounts, this original Cheviot importation was nothing “to write home about.” Apart from its natural vitality and hardiness, it had little to commend it to the rank and file of American sheepmen.

According to the Handbook of the American Cheviot Sheep Society, “the best of the American-bred sheep (with rare exceptions) were comparatively slack behind the shoulders, long on the legs, and loosely put together. They carried much lighter quarters and lacked that depth and thickness of girth, so essential to the breed.”

This frank airing of the faults of the early stock did much to alert Cheviot breeders to the need for concerted action. Using the show ring as the means of evaluating their progress, they brought in from abroad a number of outstanding rams – Cock Robin, The Gentleman, The Clansman, Sprigo, Lynigan – these and their progeny have brought about the needed spiritual revival of the Cheviot industry.

The show ring performances of U.S. Cheviot breeders at Toronto in 1956 and 1957 have raised U.S.-bred stock to a new level of international respect as regards its competitive standing with the Cheviot stock of other countries. They also demonstrate that U.S. Cheviots are well qualified to take their place creditably among the major breeds of the U.S. and Canada.

The modern American Cheviot is primarily a mutton sheep. As sheep weights go, it is definitely one of the smaller breeds. Rams in good condition mature at from 160 to 200 lbs., ewes from 120 to 160 lbs. Under favorable conditions, these weights are often exceeded.

Cheviot breeders are quick to point out that the size of the sheep is less important than the pounds of lamb and wool produced per 100 pounds of ewe, — or even more importantly, per acre of land. In an Oregon Experiment Station report on the management of sheep on hill pastures (Bull. 554, Nov. 1955), a comparison of the Cheviot with three other breeds popular in that state shows Cheviots out in front in both pounds of lamb per 100 pounds of ewe and in the percentage of marketable lamb. Says the Oregon report: “The smaller, more compact breeds … will sire lambs not as large at weaning … but a greater percentage of such lambs will be marketable because of the blockier type and high degree of fatness. Thus, if the market is demanding quality to the extent of paying for better conformation and condition … (they) find a place for crossbreeding in fat lamb production.”

The leading Cheviot breeders feel that it would be desirable to increase the size of Cheviots, provided it can be done without sacrificing any of their carcass quality, hardiness, or any of their other good qualities. Work is going ahead toward this goal, and the future holds promise of progress in this direction.

Registration and promotion of Cheviots is handled by the American Cheviot Sheep Society at Lafayette Hill, Pa., with Stan Gates as Secretary. The Society’s officers are distributed from Vermont to Oregon.

Cheviot breeders in several sections have formed local Cheviot Associations which are concerned with their local needs, but work closely with the national Society. These are the Illinois, Iowa, and Ohio Cheviot Breeder’s Associations, and the Pacific Cheviot Society.

As evolved up to this time, the Cheviot is a compact, lowest animal, thick in all the right places, and well-proportioned. Its outward appearance is highly misleading, since it does not give impression of the heavy muscling or inherent ruggedness that it actually possesses – rather, it presents a picture of ultra-refinement: a portrait of “what the well-dressed sheep will wear”.

Contrary to this picture of delicate refinement, the Cheviot is actually a rugged and vigorous sheep. Ribs are usually well sprung; the loin is wide; hindquarters are full and deep. The hind leg in the vicinity of the thigh may be unexpectedly large for the size of the animal. The earlier tendency toward high and bare shoulders has been largely overcome by the better breeders. It is clearly cited as objectionable on the score cared of the Registry Association.

The Cheviot has an alert, appraising eye and a bold carriage. The clear white open face is long, often with a nose distinctly Roman. The end of the nose is black. An upright ear is covered with fine white hair.

The breed score card allows 25 points (of a possible 100) for fleece, which is required to be long, dense, even, ¼ to 3/8 blood combing, and of distinct crimp. Rams are expected to shear 9 to 14 lbs., ewes 7 to 10 lbs. Fleeces have relatively little yolk and give a correspondingly high yield of clean wool.

Cheviot flocks are fairly widely distributed over the Eastern U.S. and adjacent Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. A number of flocks have been established on the West Coasts of Canada and the U.S. with small flocks under way in such remote and inhospitable places as Kodiak Island (off the Alaskan Coast), where sheep need to know how to take it.

A number of successful crosses have originated from the Cheviot breed. Notable among these are the Montadale (Cheviot x Columbia), and the Scottish Half-bred (Leicester x Cheviot).

The bone is light, and the legs covered with white hair from knee to hock. Wool growth ends at the knees and neck, leaving the head completely free of wool.

Can’t Judge by Wrapping

Though Cheviots may come in small packages, they contain for the breeder a surprising combination of highly desirable qualities: hardiness, long life, productiveness, and a high quality of meat and wool. Throughout the eastern and northern parts of the U.S. and southern Canada, there are vast tracts of rough, unproductive hill country that would seem to be just waiting to put to profitable use by this durable breed, that expects relatively little of man and even less from the elements.

Where there’s a really tough clean-up job to be done to convert waste land into dollars, more and more sheepmen are discovering that “Cheviots can take it!”

REFERENCES

The American Shepherd (1857); L.A. Morrell; The Story of Wool (1947), W. F. Leggett; Official Handbook of the Cheviot Sheep Society (Eng.); Handbook of the American Sheep Society (1937); Managing Sheep on Hill Pastures, Oregon Expt. Sta. Bull. 554 (1955); Breeds of Sheep, J.F. Walker (1942); Sheep Husbandry, M. E. Ensminger (1955); Wool Knowledge, International Wool Secretariat (Eng.); America’s sheep Trails, E. N. Wentworth (1948).